Risk Matrices - subjective or sensible?

I was asked recently for my opinion on the advantage a 5x5 risk matrix over a 4x5 matrix and it started me thinking. A risk matrix is meant to help categorise, prioritise and compare risks, so what difference does 5 or 4 rows or columns really make? I thought it would depend on how precisely the severity and likelihood ranges have been defined but what I found out was so much more.

I have always been mildly skeptical of risk matrices, struggling to see how all that risk data could be condensed and simplified into a single box and still remain meaningful. It turns I was right to be doubtful.

My research highlighted that there is no scientific method of designing the scale used in a risk matrix. From the numerous and varied scales I have encountered in aviation and elsewhere, the common factor is they are typically ordinal scales. An ordinal scale has no fixed distance between the levels; the numbers represent a rank position. Questions with subjective responses are often ordinal, for example, “how much pain are you in?” could be answered with “none”, “a little”, “some”, “a lot”, “excruciating”. The responses go from least to most pain, but it’s not clear whether the difference between “none” and “a little” is bigger, smaller, or the same as the difference between “a lot” and “excruciating”. This also emphasises the subjective nature of the scale. What’s excruciating to me maybe merely “a little painful” to you.

Ordinal responses may be transformed in any way that preserves their order, which in a 5x5 risk matrix could be 1-5 or 0,5,37,40 and 103. The numbers are irrelevant as long as the order stays the same.

Using the previous example, it’s obvious that “excruciating” is not twice as painful as “some”, in the same way that 70 degrees is not twice as hot as 35 degrees. Multiplication cannot be applied to an ordinal scale but this is what appears to have been done in the CAA UK’s CAP 795, Safety Management Systems (SMS) guidance for organisations. The numbers are drawing incorrect comparisons between risks, suggesting that Remote/hazardous is twice as risky as improbable/major, as a result of committing the mathematical no-no of multiplying an ordinal scale.

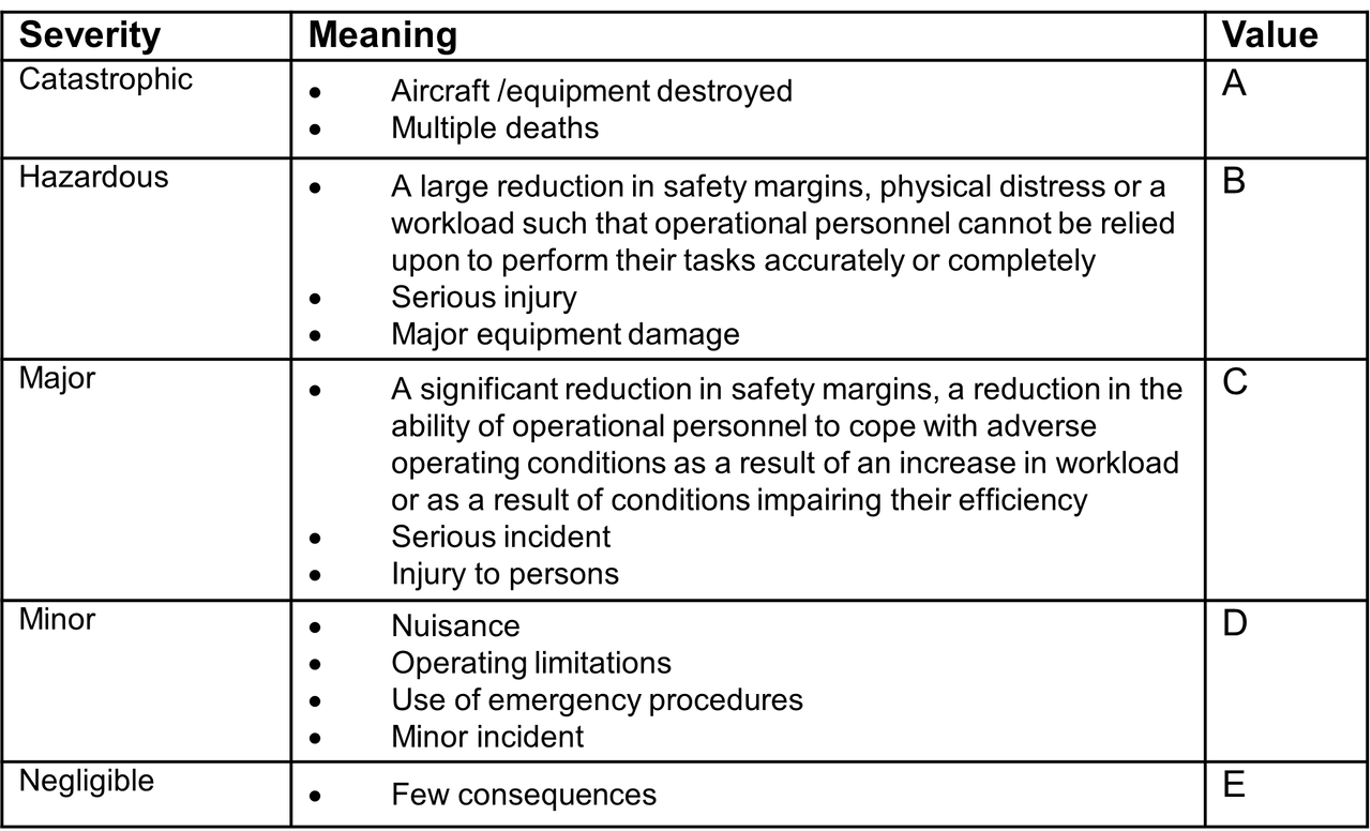

Cox has written extensively about the use of risk matrices and investigates how the use of ordinal scales can lead to errors in decision making. For me, he has named one of the most significant errors, called “range compression” which can lead to risks with significantly different values being placed in the same cell. Consider ICAO’s “Example safety risk severity table” (table 1). The boundary between hazardous and catastrophic is blurred because there is nowhere to categorise a single, or a “few” deaths. In this example, the risk of one or two deaths must be put in the same box as a total hull loss resulting in multiple deaths.

CAA UK has refined the ICAO hazardous category to a certain extent by adding “serious injury or death to a number of people” but the risk ranking still seems arbitrary. A risk that is likely to occur many times with a nuisance outcome is given higher priority (10) than a risk that may possibly occur and will result in serious injury to persons (9). The remote occurrence of death to a number of people is ranked the same (12) as a significant reduction in safety margins that has is occasional. The relative magnitude of consequences and probability is compressed, thus undermining the readily held belief that risk matrices improve communication.

Thomas, Reidar and Bratvold talk about centering bias, a phenomenon in which 75% of the probability ratings assessed were centred around 2,3 and 4, thereby effectively reducing the matrix to a 3x3. Also, probability ratings are often necessarily ambiguous and open to interpretation. A study by Budescu et al (2009) showed that “very likely” was assigned to probabilities varying from 0.43 to 0.99 because context and personal attitude to risk will always influence a person’s perception of consequence. Additionally, the words used to describe probability lead to inconsistencies; compare these two definitions of improbable: “virtually improbable and unrealistic” or “ would require a rare combination of factors to cause an incident”. We invite subjectiveness simply by the word pictures we paint.

Before summing up, I give you an interesting extract from Cox’s paper:

“..the common assumption that risk matrices, although imprecise, do some good in helping to focus attention on the most serious problems and in screening out less serious problems is not necessarily justified. Although risk matrices can indeed be very useful if probability and consequence values are positively correlated, they can be worse than useless when probability and consequence values are negatively correlated. Unfortunately, negative correlation may be common in practice, for example, when the risks of concern include a mix of low-probability, high consequence and higher-probability, low-consequence events”.

Conclusions

So what’s the alternative, given that risk matrices are so entrenched in our risk management practices? First, we need to recognise the limitations of risk matrices and educate ourselves so we are in a position to explain why they do not necessarily support good risk management decisions and by association, the effective allocation of resources.

Secondly, time spent pondering whether the probability is 3 or 4 should be invested instead in mapping out possible accident scenarios, identifying critical controls and ensuring mitigations are both adequate and reliable.

This will allow us to assign priorities to barriers/controls and assess whether the effectiveness of the barrier is tolerable; rather than prioritising and categorising a set of risks based on a flawed matrix.

Bibliography

Ball, D.J. and Watt, J. (2013) Further thoughts on the utility of risk matrices. Risk Analysis. Vol 33, 11.

Budescu, D.V., Broomell, S., and Por, H.H. (2009). Improving communication of uncertainty in reports of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Psychological Science. 20, 3:299-308.

Cox Jr., L.A. (2008). What’s wrong with Risk Matrices? Risk Analysis. Vol 28, 2.

Hubbard, D. W., Seiersen, R. (2016) How to Measure Anything in Cybersecurity Risk. Wiley:New Jersey

ICAO Doc 9859 Safety Management Manual (2018) Fourth edition

Safety and Airspace Regulation Group. (2015). CAP 795 Safety Management Systems (SMS) guidance for organisations. CAA UK.

Thomas, P. Bratvold, R.B. and Bickel, J.E. (2013) The Risk of Using Risk Matrices. SPE Economics and Management.

We’ve proud to have built industry-defining software, shaped by lived experience and backed by experts who know what’s at stake in making high-risk decisions.

Author: RiskFlag

7/25/2023